The official exchange between the U.S. and China began in February 1784 with the first U.S. merchant ship to China, the “Empress of China.” Before the independence of the United States, exchanges were made either under the control of the United Kingdom or subcontracted to other world powers. The U.S. entry to China was ironically prompted by a British sailor, James Ledyard.

He arrived in the United States after his captain, James Cook, died in Hawaii. In May 1783, he emphasized the value of the Chinese market to Robert Morris, the owner of the largest merchant firm in the United States and a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, by saying that he would run a commercial empire that the United States had never seen.

"China dreams"

Having agonized for more than half a year, Morris invested in the “Empress of China.” The investment was successful with a 30% higher return ($30,000 at the time which is worth about $1 million today). The second merchant ship he invested, the Pallas, brought $50,000. Over the next 15 years, the number of U.S. merchant ships trading with China reached more than 200, the second-highest after the United Kingdom with 400 ships. The United States emerged as China's second-largest trading partner in a short period of time.

There were three parts in the “China dreams” of the United States. It was to replace Britain as China's biggest trading partner. And it was to dominate Asia by dominating the Chinese market. Lastly, it was to open China further and to make China a more stable and rich country by establishing Christianity and democracy.

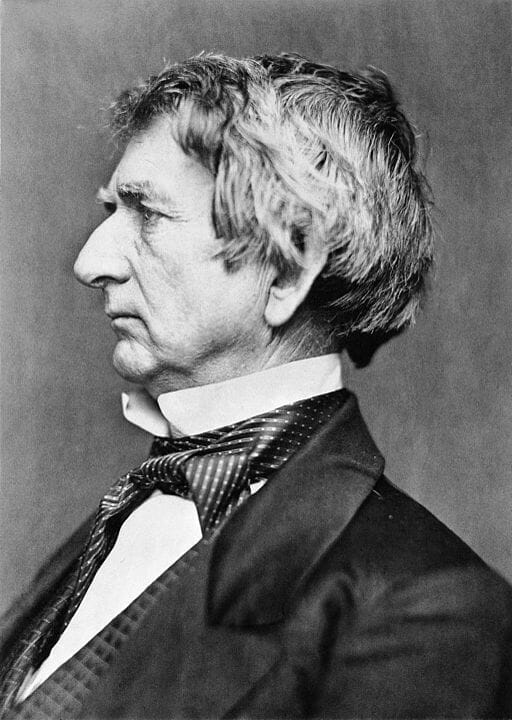

The "China Dreams" of the United States was also expressed by William Seward, who served as the Secretary of State for President Lincoln (1861-1869). He saw "Asia as the place for world hegemony." In other words, the future of the United States was the Pacific Ocean, which meant conquering the Chinese market. His belief was embodied in the passage of the bill to support the transcontinental railway project for easy access to China, the purchase of Alaska, and the amendment of an Annex in the U.S.-China treaty of 1858 (improvement of human rights in both countries).

These American “China dreams” are still in effect today. The goals of expanding opening, establishing democracy, and protecting human rights in China have more than 200 years of history. This is why all U.S. strategic reports on China start with a stance of welcoming open, stable, and strong China in the present day.

Jaewoo Choo

Jaewoo Choo is a professor of International Politics at Kyung Hee University, South Korea, and Director of China Research Center, Korea Research Institute for National Strategy.

Copyrights ⓒ Segye Ilbo. All rights reserved. http://m.segye.com/view/20210131508185