With increased global student mobility alongside recent initiatives taken by the Japanese government, there has been an upswing in the number of international students studying in Japan. “Internationalization” in this fast-changing world is seen as a way to ‘gain brain’ and meet the challenges that Japanese will face with a declining population. 1 Moreover, Japan is now keen to catch up with American and British universities in the number of international students and faculty numbers. Indeed, Japan’s national universities are accepting more international students and inviting more academics from overseas. Yet, the challenges that the Japanese education ministry and the universities face are monumental. For the process of “internationalization” the very term is yet to be clearly defined and a concrete strategy put in place. As a result there have been a myriad of approaches, harebrained schemes and spectacular bungling. And, there are many unresolved issues with the internationalization of Japanese national universities that warrant scholarly attention.

Having been invited to study in Japan for the second time as one of them at Osaka University, one of the top Japanese national universities, I was inspired to study Japanese government and university strategies over the course of three decades, since the 1980s when “kokusaika” or “internationalization” became a fashionable term in Japan’s education discourse as part of Prime Minister Nakasone’s pledge in the 1980’s to transform Japan into an ‘international country’. 2 Based on my research and personal experience as an international student, I reached a preliminary conclusion that Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and national universities should focus more on long-term, profound and qualitative approaches for “internationalization” in a way to make it more meaningful.

In English for an international audience: Osaka University's Instagram page: https://www.instagram.com/osakauniversity/

Challenges to kokusaika

Although MEXT has realized the need to become “internationalized” (kokusai-ka), it has not specifically defined or reflected on what it means to be “international”. Few scholars have identified this as an issue. A quick look at websites of top national universities and MEXT suggests that there is a general image of what “internationalization” should be and how this is regarded by stakeholders and Japanese society more generally. However, as one scholar mentions, the value, nature, purpose and function of the “internationalization” of these universities have not been fully defined or even investigated. 3 In fact, there has been scant interest in this area from Japanese scholars. For a term that has gained such traction, divergence in values and free interpretation within Japanese society could become detrimental or even dangerous. This could result in a strategy imbalance or policy paralysis as the broader framework for understanding various dimensions and scope of “internationalization” for these institutions is largely ignored.

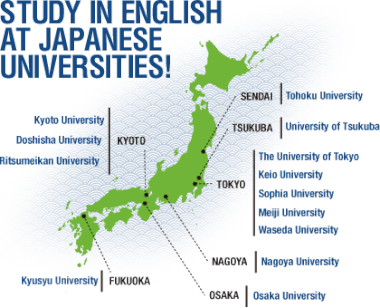

MEXT and its major stakeholders, like the national universities, have striven to promote “internationalization” by establishing ambitious projects like ‘Global COE’ (Centres Of Excellence) and the more recently established ‘Global 30’, yet none are truly focused on the long-term. While the ‘Global COE’ and ‘Global 30’ are examples of qualitative approaches undertaken by MEXT (and the 13 selected Japanese universities in case of Global 30), the major concern is the plan to attract 300,000 international students by the year 2020. When the first plan to invite 100,000 international students by the year 2000 was implemented in the last decades of the twentieth century, the target number was not met.

Yet, the new plan to double the international student numbers from the current 140,000 to 300,000 indicates the survival of the quantitative approach. Noting that the total number of students in one of the more significant international programs initiated by MEXT—the English-based Global 30—attracted only 450 students as of 2012, this target seems over ambitious. While the student number has been relatively small, the program of Global 30 itself is highly respected and valued for its quality assurance benchmarking standards. Unfortunately, MEXT stopped funding Global 30 programs as of 2014, which indicates a shifting interest towards new avenues in its path to meet the exorbitant quantitative goals it laid out. As a result, MEXT has been focusing on superficial and quantitative approaches instead. Although lofty, these approaches might not be in the best interests of the international students who choose to study and work Japan, even though Japanese society still embraces ‘Japanese-ness’ as opposed to being able to accept multi-cultural, multi-ethnic identities.

A major difference between the 1983 plan to attract 100,000 international students and the current plan for 300,000 students is the former looked at international students as guests. This means they were expected to return home after pursuing their degree in Japan and serve their home country, to better relations with Japan, and thereby become a link between Japan and other countries. By contrast, the current plan to accept 300,000 students is qualitative in nature. It is hoped that a large number of international students will stay on to work in Japan and contribute directly to Japanese society. This is an endeavour that requires much larger assistance and support by the Japanese government as well as wide promotion within Japanese society (including workplaces) for effective utilization of the highly-skilled multi-cultural, multi-ethnic graduates of Japanese universities who plan to establish themselves in Japan. This could be an overwhelming task, but it is a key challenge for the success in Japan’s quest for “internationalization”.

The Universities

Japanese national universities have been moderately successful in attracting international students and faculty to study, teach and conduct research in Japan. Yet it is vital that issues of diversity, integration, prosperity and growth and the need for wide ranging qualitative approaches are not overlooked. In a survey published by Japan’s leading financial daily, The Nikkei in June 2012, private universities like Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University (APU) or Akita International University (AIU), that were founded on the principles of a large international student body and faculty, have faired much better than many national universities recruiting multi-cultural, multi-lingual students. 4 The success of these new private counterparts in attracting and nurturing global talent indicates a need for drastic transformation in the values and structure of Japanese higher education, particularly those of national universities, whose systems date back to the values of the last century or before.

According to Naoyuki Agawa, “Japanese universities today are the products of 150 (or at least 60) years of efforts to firmly establish and run a uniquely indigenous higher education system”. 5 This structure has a predominantly Japanese student body and faculty with Japanese scholarship being preeminent in terms of textbooks and libraries. This has worked well for Japan in the past, and universities have thrived in this environment until recently. But this system is not suitable for “internationalization”. The president of AIU, Mineo Nakajima, mentions that when he tried to redesign the program for study in English at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, he was met with passive resistance, 6 and as a result, he established his own university. Expressing frustration in a New York Times article, Nakajima said, “Japan is still an intellectually closed shop and changing an existing university system is difficult”.

Graphic from the MEXT website: http://www.mext.go.jp/english/

These points correspond with my personal experience as a student at a Japanese national university. There appears to be a dire need to update the system from the top-down and to encourage the bureaucracy to be more friendly and susceptible to change or re-invention. There is a call for structural policy changes that could help the national universities in particular to compete with the newer private universities such as AIU or Ritsumeikan APU. These institutions need more flexibility and and the ability to engage more meaningfully with an “internationalizing” agenda.

Moreover, the national universities in Japan, despite efforts to “internationalize”, have been refusing to accept students who graduate from special schools that cater for ethnic minorities, such as Korean, Chinese and Brazilian nationals residing in Japan. 7 According to the School Education Act, these schools “are not qualified as regular schools because the curriculum is based on ethnic and cultural needs”. 8 This is ironic and a stark contradiction to the claim that the main goal of “internationalization” of Japanese national universities is diversification. The reason that ethnic domestic diversity is snubbed while support for diversity in international students is promoted is baffling to a non-Japanese. This also questions the substance of openness of education and diversity at Japan’s national universities, a kind where “Japanese-ness” or the values of ‘Nihonjinron’ are not encouraged but individuality is.

What is ironic is that while Chinese and Korean ethnic minorities face discrimination in Japan, 93.5 percent, or almost 130,000 international students, come from Asia. Only 2.7 percent of international students are from Europe and only 1.3 per cent from the United States (Japan Association for Student Support Organization, 2013). These numbers suggest a disproportionate ratio of Asian students, and highlight the lack of outreach to regions further afield. And, this reflects Japan’s inward-mindedness and lack of English-medium programs. So while Japanese government data suggests an upward mobility trend in international student numbers, the real issues Japan faces to achieve true “internationalization”—diversification and integration with the wider world—remain unaddressed.

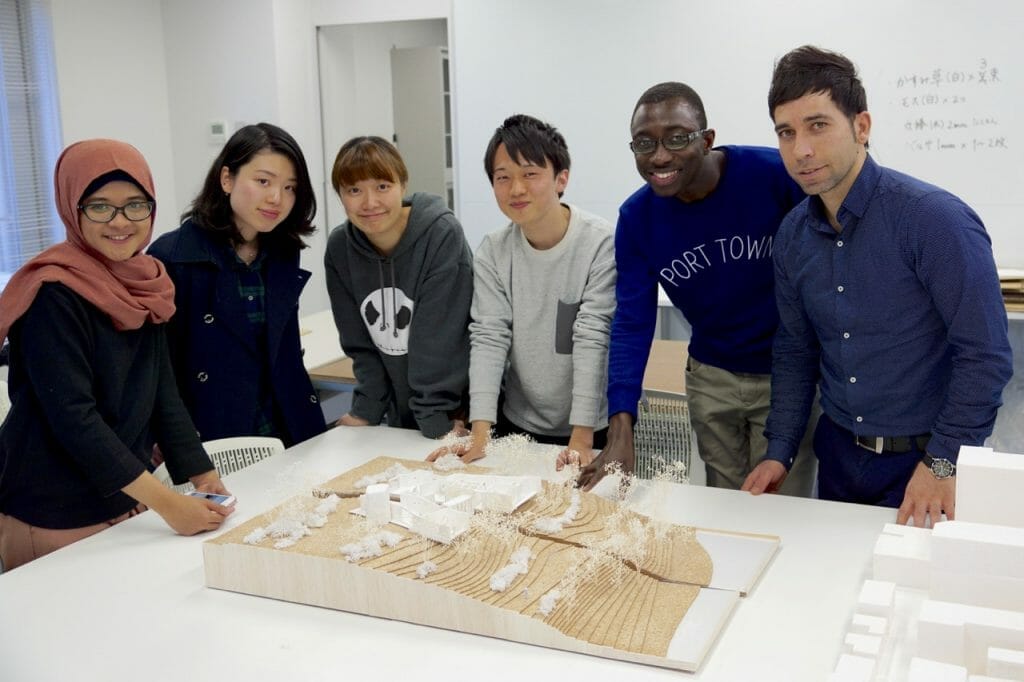

STUDENT LIFE

ompounding the challenges of “internationalization” for the national universities is the issue of integration at a different level that needs to be encouraged. This has to do with personal bonding, where foreign students need to feel as though they fit in, rather than being seen in light of the uchi/soto system where ‘uchi’ is Japan or homeland and ‘soto’ being the outside world.

Still today, the uchi/soto attitude leads to the isolation of international students; foreigners tend to clump together like vegetables without broader social integration. One research shows that over 50 percent of international students find it hard to be friends with Japanese students, and the author notes: “[Since] the number of international students is more readily measurable or quantifiable as compared to, for instance, interaction between domestic and international students, the latter has often been overlooked”. 9 Hence, “internationalization” depends also on the Japanese social environment, such as common Japanese attitudes towards foreign nationals. 10 The national universities need to promote an environment where difference in values, culture and personalities is embraced more readily and foreigners around campus are seen as the new ‘normal’, and international students are considered as part of the fabric of Japanese multi-cultural, globalized universities (and society).

THE FACULTY

Inviting international faculty members and academics is a key challenge for Japan if it wants to accomplish its efforts to ‘brain gain’. Until now, the national universities have been seen largely unwilling to do so and history has a part to play in this. Kim and Locke (2010) categorized Japan as a self-contained model where academics view the Japanese academic labour market mobility as low.

Until the 1980s, academics in national universities were considered ‘civil servants’ (or part of the bureaucracy) which meant that Japanese citizenship was key to becoming a professor at a national university. This has changed to some degree around 5 per cent of the faculty is now foreign. But even so, the number is quite low compared to Harvard or Yale, where 30 per cent of the faculty is foreign, and at Oxford and Cambridge the proportion is as high as 40 per cent. 11 The Japanese average of 5 per cent is not very encouraging. Although more research needs to be done in this area, the low numbers can be generally attributed to unwillingness of the Japanese national universities to hire international faculty on a full-time basis, meaning they are happier to give short-term (one to three year) contracts that can only be renewed up to five years. There are hardly any international faculty in the positions of deans and presidents of universities, and the need to provide equal treatment and opportunities to foreign professors is clear. For a professor whose research area is not Japan but would have sufficient opportunity to thrive in any another country, there is little incentive to teach or conduct research at a Japanese national university that gives no job security or social mobility.

The other side of this issue is the general lack of meaningful contribution by Japanese scholars to the international dialogue in their disciplines, especially in the field of social sciences. If Japanese professors themselves do not “internationalize”, a flow of a few dozen students back and forth to a university will not make it international.

Conclusion

In Whitsed and Volet (2011), the authors conclude by arguing “metaphors that stress notions of difference and otherness are problematic as they create challenges for addressing the intercultural aspects of internationalization in the Japanese context”. 12 The approaches to “internationalization” should address the intercultural and social aspect of it, as the current quantitative efforts to “internationalize” do not guarantee “internationalization”.

In Japan, where the unspoken social rules are predominant in workplaces as well as in society as a whole, foreigners generally find it difficult to thrive. On the other hand, the Japanese student’s development of his or her individuality needs to be encouraged and fostered also, even though I do not suggest a major cultural upheaval by students. Yet, the component of absolute obedience and hierarchy needs to change. Jane Knight (2011) recently reminded us that the presence of international students alone does not mean that the domestic students or even international students themselves are reaping the benefits of “internationalization”. 13 The success or failure of Japan’s ‘brain gain’ story depends on the way the stakeholders utilize the international students meaningfully. And, here I offer some ideas as a conclusion.

There needs to be more dynamic initiatives to be undertaken for knowledge creation and exchange by the national universities to promote the process of “internationalization”. Even though the government plans to increase the number of international students, there needs also the assurance of a high standard of quality, and the development an evaluation standard for the Japanese national universities is critical to this end. There is also no doubt that these universities need to provide equal opportunities for foreign professors and ethnic minorities.

MEXT and the national universities have so far only satisfied the pre-requisites of “internationalization”: international student enrolment and English programs. This is just the beginning and various challenges in terms of accountability, resource management, and most importantly qualitative expansion lie ahead. To catch up with the world’s top universities, Japan’s national universities will have to introduce qualitative benchmarking standards for its programs and encourage independent, third-party review, thereby being more transparent. In these endeavours, the MEXT and the Japanese government will have to continue being the catalysts for transformation and change.

An English poet, John Donne once said: “No man is an island, entire in itself. Every man is a piece of the continent, part of the main”. The Japanese government and the national universities have realized that, Japan is presently in the phase of a major transformation in its education sector. As a student privileged to be at one of Japan’s top university at this moment, I am happy to see the change, be part of the change and contribute to the change.

Varun Khanna

School of Human Sciences, Osaka University

REFERENCES

Agawa, N., 2011. The internationalization of Japan’s higher education: Challenges and Evolutions. Campus France.

Burgess, C., Gibson, I., Klaphake, J. and Selzer, M., 2010. The ‘Global 30’Project and Japanese higher education reform: an example of a ‘closing in’or an ‘opening up’?. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 8(4), pp.461--475.

Horie, M., 2002. The internationalization of higher education in Japan in the 1990s: A reconsideration. Higher Education, 43(1), pp.65--84.

Jasso.go.jp, 2014. Japan Student Services Organization-JASSO. [online] Available at: <http://www.jasso.go.jp/index_e.html> [Accessed 17 Jun. 2014].

Knight, J., 2011. Five myths about internationalization. International Higher Education, 62(Winter), pp.14--15.

Morita, L., 2012. Internationalisation and Intercultural Interaction at a Japanese University—a Continuing Inquiry. electronic journal of contemporary Japanese studies.

Shao, C., 2008. Japanese policies and international students in Japan.

Tanikawa, M., 2012. Japanese Universities Go Global, but Slowly. New York Times. [online] Available at: <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/30/world/asia/30iht-educlede30.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&> [Accessed 15 Jun. 2014].

Topuniversities.com, 2014. Japanese Universities: A New Era of Internationalization. [online] Available at: <http://www.topuniversities.com/where-to-study/asia/japan/japanese-universities-new-era-internationalization> [Accessed 11 Jun. 2014].

Whitsed, C. and Volet, S., 2010. Fostering the intercultural dimensions of internationalisation in higher education: metaphors and challenges in the Japanese context. Journal of Studies in International Education.

Notes:

- Horie, M., 2002. The internationalization of higher education in Japan in the 1990s: A reconsideration.Higher Education, 43(1), pp.65–84. ↩

- Burgess, C., Gibson, I., Klaphake, J. and Selzer, M., 2010. The ‘Global 30’Project and Japanese higher education reform: an example of a ‘closing in’or an ‘opening up’?. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 8(4), pp.461–475. ↩

- Whitsed, C. and Volet, S., 2010. Fostering the intercultural dimensions of internationalisation in higher education: metaphors and challenges in the Japanese context. Journal of Studies in International Education. ↩

- Tanikawa, M., 2012. Japanese Universities Go Global, but Slowly. New York Times. [online] Available at: <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/30/world/asia/30iht- ↩

- Agawa, N., 2011. The internationalization of Japan’s higher education: Challenges and Evolutions.Campus France. ↩

- Tanikawa, M., 2012. Japanese Universities Go Global, but Slowly. New York Times. [online] Available at: <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/30/world/asia/30iht-educlede30.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&> [Accessed 15 Jun. 2014]. ↩

- Horie, M., 2002. The internationalization of higher education in Japan in the 1990s: A reconsideration.Higher Education, 43(1), pp.65–84. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Morita, L., 2012. Internationalisation and Intercultural Interaction at a Japanese University—a Continuing Inquiry. electronic journal of contemporary Japanese studies. ↩

- Shao, C., 2008. Japanese policies and international students in Japan. ↩

- Agawa, N., 2011. The internationalization of Japan’s higher education: Challenges and Evolutions.Campus France. ↩

- Whitsed, C. and Volet, S., 2010. Fostering the intercultural dimensions of internationalisation in higher education: metaphors and challenges in the Japanese context. Journal of Studies in International Education. ↩

- Knight, J., 2011. Five myths about internationalization. International Higher Education, 62(Winter), pp.14–15. ↩

Thanks for this very insightful essay. Interesting stuff!

Excellent piece, well researched, which points out some gaps in our understanding of internationalization in Japan. Japan’s universities need to better clarify what they mean by internationalization and globalization. My experience is that some of Japan’s university faculty feel already burdened by an overload of classes and meetings and view this global education movement as yet another weight to their work. Just how motivated are faculty, both foreign and native, committed to globalizing the curriculum, research, and communication? That’s yet to be answered.

Thank you for your comment.

Dr. Nancy Snow wrote an interesting opinion piece for the Japan Times on a similar topic that is well worth checking out. It can be found here: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2015/06/16/commentary/japan-commentary/turning-japans-universities-into-genuine-global-players-2/#.VYuEDlwrIUF

OpenAsia